|

|

|

|

|

Traditional Economic Practices of Birhor Tribe of Chhattisgarh and Its Relevance for Sustainable Development

Dr. Rajkumar Nagwanshee 1![]() , Dr. Ashvanee Kumar 2

, Dr. Ashvanee Kumar 2![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Economics, Guru Ghasidas

Central University, Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Guest Faculty, Government Naveen Collage Kera, Shaheed Nand Kumar

Patel University Raigarh, Chhattisgarh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Indian tribes are known for their rich ethnic and cultural heritage but due to rapid urbanization and industrialization, they have been losing their unique identity. Rapid urbanization and industrialization have further endangered their culture, eroding their traditional beliefs, language, and practices. Among all these tribes of India, Birhor is one of the most endangered tribes, and it is on the verge of extinction. It is, therefore, necessary to investigate the evolving socio-cultural patterns of the vulnerable "Birhor" tribe and to put appropriate strategies and programs in place for the self-initiated preservation of indigenous tribal culture and identity. The studies on

the Birhor tribes focus on either their traditional economic practices or

their cultural erosion due to urbanization, but few have comprehensively

analyzed how these economic adaptations influence their identity and

long-term survival. Additionally, while the impact of government policies on

their settlement patterns has been noted, there is limited research on how

these policies have affected their livelihood sustainability and access to

resources. This study state about the understanding

of the inter-community dynamics between the Birhor and other tribal groups,

particularly how social discrimination shapes their economic opportunities. |

|||

|

Received 28 May 2025 Accepted 25 June 2025 Published 09 July 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Rajkumar Nagwanshee, raj.nagwanshee@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/ShodhSamajik.v2.i2.2025.22 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Chhattisgarh’s Tribe, Bihor Tribe, Tribal

Development, Tribal Traditional Practices |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Indian tribes are known for their rich ethnic and cultural

heritage. There are over 500 tribal

groups and their sub-tribal groups that reside in the country's highlands,

woods, and isolated regions. Other cultures and communities continued to be

absorbed over time. Despite this, most of the tribal communities were successful

in preserving their cultural heritage Barman (2024).

A

significant portion of the Indian population consists of tribal communities.

The world's highest concentration of tribal people from diverse cultures is

found exclusively in India Barman (2024). People who employ primitive technology, live in a certain

area, and share cultural traits are known as tribal people. Tribes are

acknowledged for their distinct ethnic and cultural traits, but as a result of rapid and extensive urbanization and

industrialization, they are losing their individual identities.

On the other hand, Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups

(PVTGs) represent the most vulnerable segment among India's tribal communities.

They largely rely on hunting for sustenance and possess a pre-agricultural

level of technology. At present, there are approximately 2.8 million PVTG

individuals, spread across 75 tribes residing in 22,544 villages within 220

districts across 18 states and union territories in India (Barman, P.K, 2024).

Historically, they lived in forests and had a nomadic hunting and gathering

lifestyle. There are two groups of Birhors based on

their socioeconomic status. Janghis is the name of the settled Birhors, whereas Uthlus is the name of the nomadic Birhors.

The Birhor tribe in

Chhattisgarh lives in severe socioeconomic conditions, largely dependent on

forest collection and basketry for their livelihood. Many Birhor individuals do

not own land and live on unauthorized land in jungles, resulting in a constant

fear of displacement. Their nomadic lifestyle, driven by the lack of stable

resources and land, leads to economic hardships. They primarily survive on a

diet of rice. They also face severe social discrimination. They are

marginalized not only by caste groups but also by other tribal communities like

the gond and kawar, who

look down upon them. Rapid urbanization and industrialization have further

endangered their culture, eroding their traditional beliefs, language, and

practices. Therefore, it is essential to examine the changing

socio-cultural dynamics of the vulnerable Birhor tribe and to develop suitable

strategies and programs that support the community's own efforts to preserve

their indigenous culture and identity Ghosh

and Chatterjee (2024).

2. Review of literature

Partha Gorai et al. (2022) state that Birhors are isolated,

primitive, semi-nomadic hunting and gathering communities of the Indian

subcontinent, subsisting primarily on forest products. They like to lead a

prehistoric lifestyle and would rather live apart from the rest of society.

They are categorized as one of the most archaic and deemed extremely vulnerable

tribal groups (PVTGs) on the Indian scheduled tribal list. At

the moment, they are having difficulty preserving their religious and

cultural identities in the regions.

Munda (2024) finds that the community Birhor have been one of the oldest tribes in India but their root rituals and cultural patterns are still alive somehow. Some Birhor communities still use their kinship terms in this manner. They share a jungle and live in the same group. They marry inside the group with different killi and use the term "kinship" before being married (they live together). The family, which includes both the maternal and paternal sides, is currently separating.

Tripathi

(2017) writes that there is a need for time to study the

changing socio-cultural patterns of life of the vulnerable tribe 'Birhor' and

to implement the right plans and programs for preserving indigenous tribal

culture and their identity with their own participation. Tribal communities

have a significant place. They give a glimpse of the ancient culture of

prehistoric India.

Bain and Premi (2019) simultaneously in their article, found that the Birhor tribe of Chhattisgarh has an impressive and extensive knowledge of traditional medicine. The remedies identified in this research deserve scientific validation through phytochemical, pharmacological, and molecular testing. The Birhor tribe must receive due recognition and royalty for their contributions. Despite being classified as a highly socio-economically marginalized ethnic group, their deep understanding of medicinal practices highlights an intense connection with nature and a strong ecological awareness.

3. Objectives and

research method of the study

1) To examine the

traditional economic practices of the Birhor tribe in Chhattisgarh

2) To study the

changes in livelihood and cultural practices of Birhor tribes in Chattisgarh

3) To study the

sustainable livelihood and cultural preservation of the Birhor tribe

The study is descriptive and has a qualitative research

approach, using a comprehensive review of existing literature to investigate

the traditional economic practices and their adaptation in the Birhor tribe of

Chhattisgarh. The study relies on secondary data sources, including existing

literature, research articles, and reports from government agencies, academic

journals, and other relevant publications.

4. The Birhor and their population

distribution

The Birhor are a tribal

group of people who live in the forests of India. The word

"Birhor" is a combination of the words "Bir" meaning jungle

and "Hor," meaning man. They are skilled at trapping animals and

weaving ropes. They are part of the Mundari group of tribes. They

generally speak the Birhori language, which is part

of the Munda group of languages. The Birhor tribes are a special backward

tribe in Chattisgarh state. In India, according to

the 2011 census, the total population of the Birhor tribes is 3108, distributed

as 1526 male and 1578 female. In Chattishgarh state,

they are mainly distributed in Jashpur, Surguja, Raigarh, Bilaspur, And

Korba districts. In the Raigarh district, they are

known by the name birhul, while in Bilaspur, they are

known as Manjhi. In Bilaspur, they are found in six villages, i.e. Khemarpara, Umaria Dadar village,

Koilarpara Village, Belgahan,

Devera, Semaria, of Kota block. In Korba, they are mainly distributed in Kodar, Sirpur, Dhumarkachar, Tonganala, Makhanpur, etc. The Birhor tribe is a semi-nomadic,

hunter-gatherer community living in Chhattisgarh, India's forests. They

are a special backward tribe of Chhattisgarh.

According to the 2001–2011 census, there is a significant

difference in the Birhor population in Chhattisgarh. The districts of Bilaspur, Korba, Jashpur, Raigarh, and Surguja are home to the majority of Chhattisgarh's Birhor

population Mather

and Kasi (2021). According to the 2001 Census, the Birhor

population was 3,744. However, a slight decline was observed in the 2011

Census, which recorded a population of 3,104. In 2011, there were 838 Birhor

households in Chhattisgarh. Data from the Tribal Research Institute indicates

that the current Birhor population is slightly higher than the figure reported

in the 2011 Census Mather

and Kasi (2021).

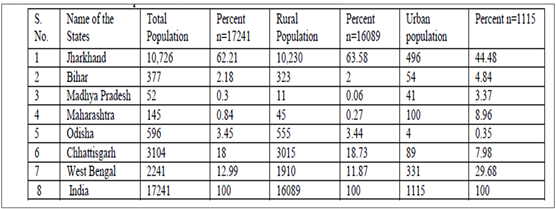

Table

1

|

Table 1 The Distribution of the Population of the Birhor Tribe in India and the States |

5. The Economic Depency

The Birhor tribe is known for their hunting and gathering skills. They also make ropes from the fibers of native trees and creepers and sell their handmade rope and forest goods in nearby markets. Some of them collect and sell honey. They speak the Birhori language, which is part of the munda language family. Their language has similarities with the Santali, Mundari, and Ho languages. The "primitive subsistence economy" of the Birhors has been based on nomadic gathering and hunting, particularly for monkeys. Some of them have settled into stable agriculture. They also trap rabbits and titers (a small bird) and collect and sell honey. Due to the combined effect of changed circumstances and government policies, some Birhors have adopted settled agricultural economies in recent years Premi (2014). Despite that, their traditional tendency to lead a nomadic life has not gone away.

The Birhor tribe gives

more importance to paddy cultivation. Along with farming, they also sell bamboo

baskets, ropes from the Nara plant and collect Tendu leaves and fruits, chironji, Mahua etc from the jungles so that they could run

their household. These people also do animal husbandry, such as goats, cows,

and chickens. And when their food material (paddy-rice) gets over, they dig out

Nakoua Kanda, Dete Kanda, Pithas

Kanda or lage kanda from

the jungle. They eat it by roasting or boiling it. They make the Dholak, Behanga etc. From the wood of trees called Saleha, pote and sell them. The people of the Birhor tribe are

engaged in agriculture work. They also used to make ropes from the bark of the Mohlain tree and sell them. In present, the use of cotton

and plastic rope has ended the rope-making business.

The Birhor tribe specializes in rope-making using fibers from specific vines like lama and udal, and this craft is the basis of their livelihood. They make five main types of ropes: 1. 'doga' for tying cattle, 2. barahi, for drawing water from wells, 3. Jhal barber, for tying multiple cattle during harvest, 4. Mukar, for cattle decoration, and 5. Jote, used in bullock carts. Apart from ropes, they also make topa, which are small bark baskets for extracting oil from seeds like safflower and baru, and shikwar, which are rope nets used for utensils and other household purposes. Hunting, although a secondary activity, still plays a cultural and subsistence role in their lives. Before hunting, a ritual is performed in which a rooster is sacrificed, with a Pahan (priest) praying for protection from dangers like wild animals and snake bites. The elders possess traditional knowledge, including chants and sounds that attract animals. The tribe hunts various animals, including monkeys, wild boars, squirrels, and birds, using dogs and specially designed snares, and catches fish using traps such as Kaanta and Kumni. Meat obtained from hunting is often sun-dried and stored for times of scarcity, although they believe hunting makes a lesser economic contribution than their rope-making trade.

6. Ethnicity

The Birhors, along with the Munda and Santhal, belong to the proto-australoid group and are characterized as dark-skinned (Malanoderm), short-statured, long-headed, wavy-haired, and broad-nosed Roy (1925). Scholars have debated their racial classification, with Risley (1902) identifying them as Dravidian, while Rougree (1921) placed them under the australoid group. Hutton (1933) described them as one of the wildest tribes in Chotanagpur, living in dense forests. Adhikary (1984) classified them as hunter-gatherers, noting that their social structure does not follow a clan-lineage-based segmentary system. Their religious beliefs include worship of sing-bonga and deities like Lugu haram and Burhi mai, with rituals performed in the months of paus-magh (December -January). They distinguish between two categories of ancestral spirits—hapram, who reside in the supernatural realm alongside the Bonga, and charging, signifying a nuanced belief system. The Birhors are divided into several totemic clans named after plants, birds, animals, rivers, and other natural elements. Verma (2004) noted that the Birhors of Jharkhand still live in a primitive stage, particularly the Uthlu Birhors, who show little interest in building permanent houses.

7. Sociocultural characteristics

The Birhors are classified into two groups: the wandering Birhors, known as Uthlus, and the settled Birhors, called Janghis. They have a long legacy as their ancestors were among the first to inhabit indin's wild forests, paving the way for other tribes. The Birhor tribe symbolizes persistence, as they continue to survive despite continual mistreatment, using strategies unparalleled in the so-called "civilized" world. A vanishing nomadic community, they are hunter-gatherers, rope makers, and isolators, often living in poverty. Primarily found in the hilly areas of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Odisha, Bihar, Maharashtra, And Madhya Pradesh, their main domain remains Jharkhand. They live in small bands called tandas, following a patrilocal family structure with the father, mother, and children as core members. Traditional inheritance follows the male line, and husband-wife relationships are notably cordial.

8. The attire of the Birhor tribe

The attire of Birhor tribes resembles that of their settled neighbors, blending traditional Indian dress with some Western influences, while women have a fondness for ornaments. The women generally wear a Shari with Blauze, most of the time women wear Scarff on their head to protecting from sunsine. Elderly males generally nacked wearing the dhoti, but the new generation in the present era wears pants and a shirt as the effect of modern Western culture.

9. Religious life

The Birhor economy is a blend of forest-based activities, agriculture, and labor. The term "Birhor" means "man of the jungle," so their traditional magico-religious beliefs closely resemble those of the hos, with Mundari deities such as Singbonga (the sun god) and Hapram (ancestral spirits) holding high esteem. Hapram is considered just below the bonga in their spiritual hierarchy. The Birhors believe that the entire universe was created and is presided over by Singbonga and his wife, Chandu Bonga, who are worshipped in the months of pous and magh Premi (2014). Singbonga is revered as the supreme god by the ho, Munda, Bhumij, and Santhal tribes, Singbonga represents the sun god and is associated with light, life, and fertility. His worship is an integral part of the tribal religious practices and rituals, often celebrated with grandeur and devotion Wikipedia (2025). Due to interactions with their Hindu neighbors, some Hindu deities like Debimai, Kalimai, And Mahadev have also been incorporated into their pantheon.

10. Food and food habits

The Food habits of the Birhors in Jharkhand and Chattishgargh highlight their deep connection with forest food and nature. As traditional hunters and gatherers, the Birhors remain largely dependent on forest resources, shaping their socio-cultural and religious life around nature, including values, attitudes, and conservation practices Sahu (2001). Their diet consists of fruits, flowers, leaves, mushrooms, and hunted animals. Still, the study also revealed significant nutritional deficiencies in their food intake, leading to common health issues like malaria, dysentery, fever, and skin diseases due to unhygienic living conditions. Improving their health includes promoting allopathic medicine and conducting periodic health check-ups. Their settlement patterns note that they change their place of residence seasonally, typically four times a year and sometimes up to six times, based on convenience Sahu (2000). They were completely reliant on the forest, and they do not domesticate cattle. Sahu (2001b) further emphasized that the Birhors are increasingly exposed to external influences, mainly through economic interdependence and development programs, leading to shifts in their attitudes, aspirations, worldview, and material culture.

11. The Origin (Myth) Story of the Birhor Tribe

There are many stories about the Birhor tribe. According to one myth, a mother had two sisters. Birhors were born from one sister and the child born from the other sister was called Mahkool. Once, both the brothers Birhor and Mahkool went to graze buffaloes in the forest. Tying their buffaloes to a wild creeper in the forest, they went inside the forest to cut the wild creeper. On returning after cutting the jungle creeper, he saw that Birhor's buffalo had broken the rope and gone somewhere else, while Mahkool's buffalo was found tied there. Then Birhor told his brother Mahkool to take his buffalo and go home, I am going to find my buffalo. Saying this, Birhor started towards the jungle. On the way, he saw a wild creeper, which he started cutting, and he forgot about finding the buffalo. In due course, while cutting the wild creeper, he started living in a mountain called Veer. Due to living in Veer Mountain and continuously making ropes from wild creepers, people started calling him Birhor (Haribhumi, 09/04/2025).

According to another myth, once lord mahadev went to the jungle to hunt with an axe and a chisel. While hunting, he crossed forty jungles, and being distressed with hunger and thirst, he quenched his hunger by eating fruits and drinking water from the drain. After a little rest, he felt like dancing and singing. He cut down a tree and, made a dholak, and started looking for prey to put the skin on it. Then his eyes fell on a monkey sitting on a tree. He hunted it and put its skin on the dholak and started playing and dancing. Later he called the nearby Birhor people and asked them to eat the meat of the dead monkey. From that day onwards, Birhors came to be known as bandar pakdwa (Haribhumi, 09/04/2025).

12. Death rituals

According to the Birhor, older adults die and eventually reincarnate as ancestral spirits. Death in childhood or youth is viewed as regrettable because such spirits become Bhuta-Preta (bad or restless spirits), whereas death in old age is viewed as normal and beneficial. These ghosts are thought to harm people until they reincarnate and finish their natural life span. The burial customs of the community are followed by a week-long period of pollution. Rituals of cleansing, such as washing clothes and utensils, are carried out on the seventh day. Men shave as part of the grieving process, and women take a cleansing bath.

13. Political organisation

The Birhor 'tanda' is a community cluster composed of families from various clans formed for collective activities such as food gathering, hunting, and rope making. Each tanda is led by a head known as the 'naya,' who serves as the group's social, political, and religious leader. Assisting the naya is the 'kotwar' or 'diguar,' whose primary responsibility is to announce the timing and schedule of the panchayat meetings. The panchayat, involving the heads of families, oversees the enforcement of customary laws. Individuals who violate these customs are judged and penalized according to community decisions. The panchayat also handles serious issues such as rape, adultery, divorce, and domestic abuse. In cases involving disputes between different tandas, an inter-tanda panchayat is convened. These decisions are respected and followed by all, as the entire community participates in both the judgment and its enforcement.

The Birhor are divided into two groups: the 'uthalu' (wandering) and 'jaghi'

(settled) Birhors. The uthalu

Birhors, due to their nomadic lifestyle, are largely

unaware of their political rights and seldom participate in elections or

government programs. Many do not even possess voter identification. In

contrast, the Jaghi Birhors,

who lead a more settled life, are active voters and exercise their franchise

during elections for local and national representatives. The Birhor are neither

supporters nor members of any political parties many Prasad et al. (2024)

14. Health status of Birhor tribes in India

In addition to having extensive traditional knowledge of medicinal herbs and natural healing, the Birhor communities are also facing malnourishment, substandard living circumstances, and restricted access to contemporary healthcare. Their health status is both fragile in the current setting and resilient in traditional ways due to this dual reality. A delicate balance between traditional resilience and contemporary fragility can be seen in the health status of the Birhor tribe in India. They are one of the PVTGs, frequently deal with issues like poor maternal and child health, a high frequency of infectious diseases like tuberculosis and malaria, and hunger. Their distant living arrangements, lack of access to potable water, inadequate sanitation, and inadequate medical services are the main causes of these problems. Infant and maternal mortality rates remain high, as institutional healthcare services are either absent or underutilized because of cultural barriers, mistrust, and logistical challenges.

They use traditional practices to prevent and treat illnesses in spite of these challenges. They have extensive understanding of herbal therapy and cure a wide range of illnesses, including infections, fever, wounds, and stomach issues, using native plants, roots, and herbs. Overall physical health is maintained by their lifestyle, which consists of a natural diet derived from forest products and continual physical exercise through hunting and gathering. In their traditional health system, community-based care and spiritual healing are equally crucial. Traditional healers and shamans perform rituals for mental and emotional well-being since illnesses are frequently seen as spiritual imbalances. Even if these conventional methods help maintain health to some extent, they are not enough to deal with more serious or contemporary health problems. Their ancient wisdom and contemporary healthcare systems need to be connected. While honoring their indigenous customs, providing them with mobile healthcare units, dietary support, and culturally sensitive health services will greatly enhance their health outcomes. In this sense, the Birhor community can gain from both modern medical treatment and traditional wisdom.

The Relevance of Traditional Ecological

Knowledge and Practices of Birhor Tribe

The Birhor tribe has historically lived in

forests, and they base their way of life on living in harmony with the natural

world. Their activities have relevance

for current debates on sustainable development as well as for cultural

preservation. Hunting and gathering is

one of the major livelihood functions of Birhor Tribe. They collect firewood, honey, fruits, roots,

tubers, medicinal herbs, and other small forest products. They use traps to hunt birds and small

animals only while preserving the natural equilibrium. They are adept at creating useful objects

like baskets and bamboo ropes. These are

renewable resources that grow quickly, and their methods use them without harming

the environment. Their centuries-old knowledge of ecosystems is crucial for

preserving biodiversity. Their way of

existence is climate-adaptable and produces very little carbon footprint. In

addition to economic measures, they always have an alternative development

model, such as development with dignity and based on ecology and community

well-being. They have a sustainable and community-focused lifestyle, and their

traditional traditions demonstrate minimal environmental impact. By recognizing

and integrating such traditional knowledge into modern sustainability measures,

it is possible to address climate change, promote equitable growth, and

safeguard biodiversity while also respecting tribal rights and culture.

In order to

maintain soil fertility and avoid synthetic inputs, they engage in organic and

subsistence farming. They can direct

agriculture and agroecology toward climate resilience, particularly for

smallholder farmers dealing with unpredictable weather. They preserve

biodiversity by their in-depth knowledge of plants and animals and their

considerate interactions with the forest, which indirectly contributes to the

achievement of SDGs 15 (Life on Land) and 14 (Life Below Water) through

upstream practices. Furthermore, because

they employ herbal remedies and conventional medical methods, they support SDG

3 (Good Health and Well-Being).

Contributing to a Low Carbon and Minimalistic Lifestyle As discussed in

SDGs 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and 13 (Climate Action), their way

of living generates almost no carbon emissions and produces very little trash.

Additionally, the Birhor tribe may teach modern civilization about the

Community-Centric Governance method.

According to SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), they frequently make

decisions together while respecting elders and the wellbeing of the community.

They live in harmony with their surroundings

since they are forest dwellers who have a strong bond with nature. An important lesson in ecological balance can

be learned from their capacity to satisfy their requirements without

endangering the ecosystem. At a time

when industrialization and excessive consumption are harming the environment,

the Birhor philosophy of resource sharing, minimalism, and zero-waste living

offers a different paradigm that encourages sustainability. The sustainable use

of natural resources is one of the most important lessons to be learned from

the Birhor way of life. Their

livelihoods rely on locally accessible, renewable resources, such as organic

farming, collecting forest products, and weaving rope from bamboo. Their

mutually respectful and consensus-based communal governing systems provide a

model for inclusive and participatory governance in today's fractured

nations. The values that the Birhors uphold by prioritizing environmental conservation

and community interests are highly compatible with contemporary sustainable

development objectives. Essentially, the

Birhor community can teach modern society how to live more responsibly by

consuming less, wasting less, maintaining a greater sense of community, and honoring the environment.

15. Government effort to develop the community

The Indian government is encouraging them to stay in one place and has also provided them with houses under various programs. Apart from the house, they are also being provided blankets, clothes, food grains and mosquito nets. Non-profit organizations like Bharat Sevashram Sangha and Ramakrishna Mission have initiated efforts to rehabilitate them in permanent camps in different localities. Apart from this, some of the programs include free schooling, free lunch for children, free medical care for both indoor and outdoor patients, jobs in locally owned handlooms and more. The government has also implemented several programs to help them, including birsa housing, goats and poultry, agricultural tools like hoe (Santa), pension for the elderly, social security pension for both men and women, and rearing and supplementary use of goats and chickens. Every family has an Antyodaya card, which entitles them to monthly free food grains, including rice, wheat and kerosene. However, some people are believed to spend the money they get from the government by selling local beverages. Many of them start drinking alcohol early in the morning.

16. Conclusion

The Birhor tribe of Chhattisgarh is a distinct and long-lived group with deep ties to the forest, subsistence customs and indigenous knowledge systems. Their core economic activities—small-scale farming, hunting, gathering and rope-making—emphasize a self-sufficient lifestyle that is strongly correlated with natural resources. Even though they are classified as a particularly vulnerable tribal group (PVTGs), their traditional knowledge—especially in areas such as herbal medicine and rope craft—reflects a sophisticated ecological understanding that deserves scientific recognition and documentation. However, industrialization, modernization, and changing socioeconomic conditions have caused rapid changes in their way of life. Their primary economic activity, rope production, has declined due to the increased use of synthetic alternatives. Hunting and gathering have taken a backseat, and while many Birhor families have shifted to small-scale animal husbandry and sustainable agriculture, their financial situation is still precarious. Social problems, including drug addiction, illiteracy, and health problems, partly caused by poor diet and poor sanitation, still impact the community. In addition, cultural changes brought about by exposure to outside influences, particularly among younger generations, risk eroding their traditional knowledge systems and values. Various governmental and non-profit entities have undertaken developmental projects in the areas of housing, healthcare, education and livelihood support. Despite the fact that these initiatives seek to improve the socioeconomic conditions of the people, their effectiveness has been uneven due to a lack of community participation and flexibility. The Birhor's reluctance to leave the forest permanently and settle down emphasizes how important culturally aware and inclusive development strategies are. The government, along with NGOs like Ramakrishna Mission and Bharat Sevashram Sangha, has implemented various welfare schemes for the Birhor tribe, including housing, food supplies, healthcare, education, and livelihood support. Despite efforts like free schooling and skill development, many youths return to their villages, resisting long-term relocation. Some beneficiaries misuse the aid, selling resources to buy alcohol, which remains a concern in the community. If their traditional knowledge is carefully conserved and incorporated, it can serve as an inspiration for laws and procedures that tackle issues like social injustice, resource scarcity, and climate change. Respecting and learning from such indigenous communities is about preserving culture and enriching our collective future.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bain, B., & Premi, J. K. (2019). An Investigation on The Ethnogynecological Medicinal Knowledge of the Birhor Tribe of Chhattisgarh, India. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 12(11), 5138–5150. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-360X.2019.00890.4

Ghosh, D., & Chatterjee, D. (2024). Birhor Society and Culture: A Study on Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups of Jharkhand, India. International Journal of Research and Review, 11(6). https://doi.org/10.52403/ijrr.20240622

Kasi, E., & Mather, G. S. (n.d.). Adivasis and Affirmative Action Policies: An Ethnographic Appraisal of PVTGs.

Mathew, G. S., & Kasi, E. (2021). Livelihoods of Vulnerable People: An Ethnographic Study Among the Birhor of Chhattisgarh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 31(1), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/10185291211007924

Munda, A. (2024). Birhor Way of Life: Balancing Ecology, Economy, and Kinship. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews.

Panna, A., & Munda, Abhijieet. (2024). Resilience and Transformation: The Story of Birhor Settlements in Jharkhand. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews, 11(1).

Prasad, B., Chauhan, A., & Mahto, R. (2024). PVTGs in Jharkhand: An Anthropological Perspective (Particularly

Vulnerable Tribal Groups). Prabhat Prakashan.

Premi, J. K. (2014). Birhor: The Inconsequential Extraordinary

Primitive Tribal Group (PTG) of India. Research

Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(4),

366–369.

Sinha, A. K., & Banerjee, B. G. (2004). Birhor II. In Ethnographic Atlas of Indian Tribes (pp. 232–247). Discovery Publishing House.

Tripathi, S. (2017). Birhor and Their Culture: An Ethnographic Account of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group of Chhattisgarh. In Jal-Jangal-Jameen Aur Janjatiyan. Triveni Seva Samiti Sohbatiyabagh.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhSamajik 2025. All Rights Reserved.